The Real Wild Woman

Summer is well underway. It’s been a fiercely hot and dry season, making it feel like the inside of a sauna wherever I go outside.

It’s put a crimp in my usually busy outdoor season, but there is a bonus: berries are coming into season a little early.

The most coveted around here is the wild blueberry. These little juicy gems are at their peak from mid-July to at least late August. The heat has made them ripen faster…where they are available. A combination of a mid-June heavy frost and bugs have caused most of my usual berry patches to be sans fruit.

There is one near my home almost guaranteed to have berries every year, but it’s a hike to get to it.

No, I won’t disclose it. There is an unwritten rule here that one never reveals their blueberry honey holes, lest someone picks it before you. People are protective of their patches here, even though I’m sure most wouldn’t want to venture that far to pick a basket.

Before venturing out for the day my father gives me something rather prophetic, a training cap gun for field retriever trials.

Since I’m going out into the deep bush, he says it’s best to bring something we call “bear bangers,” noise makers in case there is an encounter. They are active this time of year as the fruit becomes available.

Setting out it’s a mine field of marshland. Recent rains have filled dry fields and creeks. A little fancy footwork is needed to get around the mud puddles and loose rocks. My father and uncle cleared a trail for all-season recreation, making it a little easier to negotiate the notoriously thick brush.

I get about halfway there and I am stuck with the feeling I am not alone, then a noise in the trees in front of me to confirm it.

Coming down a jack pine in front of me is a tiny black bear cub.

Then it went from “awwww” to “aw, shit” real fast when momma bear appeared from behind the trees, stood up and let out a loud huff to let me know she disapproved of my presence.

My first ever direct encounter with a bear and cub.

I try to scare both off with a loud stomp and shouting, only to have the cub zip up the tree again and mom stand her ground. A couple shots from the cap gun sends her running, but not up the tree as I hoped, she bolts into the bushes across from her cub.

Now this is a worst case scenario. Mom on one side, cub on the other. Truly between mother and cub. The absolute nightmare of any outdoors person. I can hear her bellowing and stomping the ground, and I see her cub nestled in the tree. Little one isn’t going anywhere, and neither am I. All I can do is back away slowly and retreat to a safe distance about 100 metres away.

Black bears are small, about the size of a human in most cases, but they are powerful, the equivalent tackling power of a pro football linebacker, not to mention three-inch claws and a mouthful of teeth. Attacks are rare, but the protective instincts of mother bears are legendary.

Waiting isn’t an option, this could take hours before they move on.

So I put a call into dad, who offers to come get me and give me a ride on his ATV to the patch from another trial a couple kilometres away.

Sounds easy, right? It would be accept it meant driving beside a railroad track on an angle, basically hanging off the side so we don’t tip, then the actual trail is washed out from recent heavy rains. I spend about as much time running ahead to meet my dad while he negotiates what’s left of the trail, broken rocks, mud and sand.

This is the hardest I’ve ever had to work just for a couple pails of berries.

Once I get there we are sure we’ve out-maneuvered the bears, but of course to remain weary.

But it was worth it. I am greeted by hillsides and open spaces covered in bushed laden with big, juicy blueberries.

Where exactly this is I can’t say. Foragers do not give up their spots. However, you can find your own by looking out for a few aspects of the environment.

Jack pines. Blueberries thrive in acidic and sandy soil where jack pines grow.

Areas of recent burning or clearing. Blueberries are frequently the first plant to grow back after a forest fire or recent tree clearing.

The best berries are found around large rocks and boulders, which we are abundant in in northern Ontario. Radiant heat keeps the bushes warm, allowing the berries to ripen even at night, which makes them grow super big, sweet and juicy.

There is an art to picking blueberries. You want to do it in such a way where you don’t damage the bushes or the berries themselves. It is best to pick then the bushes have plenty of ripe berries, which are easy to identify as they will be plump, deep blue and have a slight wax-like coating on their surface.

The gentlest way is to get your hand under a cluster of ripe berries and with your thumb, forefinger and middle finger and carefully pinch and pull until they come off the branch. With practice you can gather a handful in this manner and hold them in your palm. Then simply pour the berries into a pail.

My father taught me this technique. I find it is the most efficient method to pick a bunch of berries at once and minimize tearing leaves, breaking branches or picking unripe berries.

You may still do that, but this makes it less likely. It is a slightly slower method than grabbing handfuls, but in the end, you will be rewarded with a bucket of clean berries with little debris to pick out later, which will make sorting and storing much easier, as well as preserving the bushes.

During the picking process you will also have to assess he quality of the berries. Not every berry will be suitable for keeping, there will always be a few that you will find overripe, partially eaten or diseased. These can be quickly discarded, but again, this is why sorting after is of utmost importance.

While picking my favourite technique is to take a smaller pail, say, a small margarine or other spread container with a lid and fill it first, then dump it into a larger bucket. It makes picking go by faster and minimizes risk of spillage, or at least makes it easier to recover any lost berries.

I’ve had a few cases where I spilled the picking bucket. Nothing kills your drive to gather than seeing the literal fruits of your labour roll away into the dirt.

And while out on the land safety is of utmost importance. When I’m out that far I always carry enough water to stay hydrated, sunscreen, bug spray (they will drive you crazy) hat, sturdy shoes, and a phone. I recommend knowing if you have cell service before going.

I also suggest bringing something to sit on, like a folding stool or even a box. Picking low bush blueberries requires a lot of squatting and crouching. Save your knees the agony.

And of course, when out in the wild, keep your eyes out for wildlife. My bear companions were not far away from where I was picking, so it was no surprise to see them again on a nearby hill zigzagging their way up and down as they foraged, eventually wandering off in the opposite direction of where we met.

From a distance the sight of a mother bear and her cub is adorable, but I stopped frequently to keep an eye on where they were going. So long as you keep plenty of space between you, it should be fine. Just remember this is their home, we are just here for a visit and you have to respect them.

Another point about bears is if you see a female (sow) and cub odds are you won’t see a male (boar). Females head to places where males are not to protect their cub and mothers give each other a wide berth, so the odds of seeing another are slim and I walk on the trail again and head for home without too much worry. I’m still cautious, though, in the event I am wrong.

To make this worth my time I picked several pounds. I tend to use a lot of berries in cooking, therefore I pick a lot.

Once home I prefer to put the buckets in the refrigerator as-is to let the berries cool and firm up for a day. One of the things I love about blueberries is they are one of the easiest to freeze and last a very long time. Pour out the berries onto a wide baking tray but do not wash them as this makes them fragile and they could release their juices.

Only wash berries right before use. Pick out any unripe berries and debris like leaves and twigs. Spread them out in an even layer and lay flat in a freezer. In about two to three hours they should individually flash freeze solid. Once frozen, they can be poured into freezer-safe bags and stored for a year or more.

Me, I like to keep a few out for adding to cereal, shortcakes, pancakes, or just to snack on. They keep well in the fridge for up to three weeks in a covered dish.

Bushes weighed down with ripe berries are exactly what you want to find when picking.

A mother black bear wan’t happy to see me while foraging with her cub.

The cub scurried up a tree while his mother had a stern talking to for me.

A gentle hand is needed to pick berries.

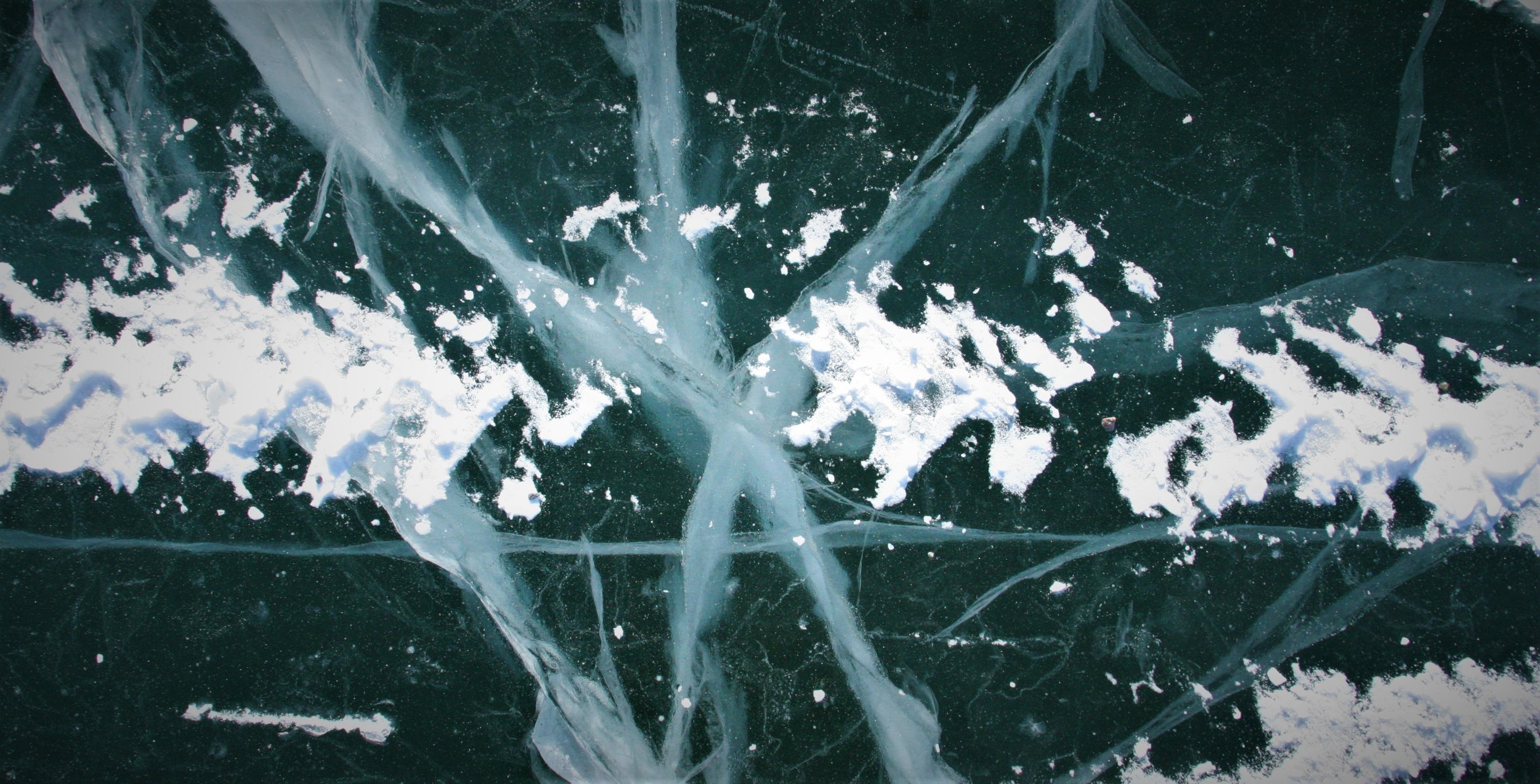

Foraging for berries in northern Ontario is hard work, but the workspace is beautiful and peaceful.

Once you get your berries home, pour them on trays to sort and look for debris.

Remove any twigs, under ripe berries, leaves and bugs (there will be a few hitchhikers.)

Once the berries are sorted, lay them out in a single layer on a baking tray and place in a freezer.

Once the berries are frozen, they can be easily poured into a bag and stored.